CHARLOTTE, N.C. — Meteorologists following the tropics since the beginning of the year always knew that it was going to be an active 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season. What’s played out so far this year, however, has been hard to count, let alone comprehend. Here are some quick, notable facts on what we’ve seen this year in the Atlantic Basin.

- With the formation of Tropical Storm Arthur on May 16, 2020 became the record sixth-straight year to have a named storm before the official start of hurricane season (June 1).

- As of this writing on September 30, the 2020 season now has 23 named storms so far.

- The previous record for most named storms before October was 17 in 2005.

- 20 of the 23 named storms this year have set records for the earliest formation for their respective letter.

- Five named storms formed in July, matching 2005 for the most active July on record.

- A record seven named storms made landfall before September.

- 10 named storms formed in September, making it the most active single month for tropical activity in the Atlantic Basin ever.

- Nine named storms have made landfall in the United States, tying a record that has stood since 1916.

- With winds of 150 mph, Hurricane Laura has become the strongest storm to ever make landfall in Louisiana.

- Tropical storms Wilfred, Alpha, and Beta all formed within six hours of each other, breaking the record for the shortest timespan between the formation of three named storms.

- The 23 named storms so far is only second to the 2005 season, which had 28 tropical storm formations.

Despite the rapid-formation of tropical storms, there has been a noticeable lag in terms of hurricanes and major hurricanes (Cat. 3+). As of this writing, the 2020 season only has eight hurricanes so far, and only two of them have reached Category 3 (111 mph+) or higher. For reference, 2005 saw a staggering 15 hurricanes form, seven of which reached major hurricane status. When comparing to the season that saw monster hurricanes such as Katrina, Rita, and Wilma, it seems that 2020 has been more quantity over quality. Why is this the case, you might ask? Let’s go more in-depth.

Sea-Surface Temperatures

One of the biggest, if not the biggest, factors for tropical cyclone development is sea-surface temperature, also known as SST. One of the first things people learn about hurricanes is that they form over open, warm water. In general, ocean temperatures at the surface need to be at least 80-82º to support tropical storm development and growth; the warmer, the better. As you can see above, temperatures across the Atlantic Basin are well into the 80s this month. September and October typically see the warmest ocean temperatures out of any other month of the year. According to the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), May 2020’s global land and sea surface temperature tied with 2016 as the warmest on record. Although the data for September’s average oceanic temperature has not come out yet, it can be reasonably inferred that it is on the same track as what we saw this past May.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that warmer temperatures mean more tropical storms and hurricanes. Recent data from this year also suggests that it means more rapidly developing storms, as well. Here are four storms I’ll point out here that rapidly intensified within 24 hours below.

Hurricane Hanna

The eighth named storm of the year, but only the first hurricane, Hanna was a weak tropical storm with core winds approaching 45 mph merely 24 hours before making landfall along the Texas coast. When the storm made landfall, however, its core winds had doubled to 90 mph.

Hurricane Laura

The second hurricane of the year joined Hanna as the second storm this season to undergo rapid intensification. Laura struggled to take shape over its journey through the Caribbean, but as it entered the Gulf, warm water over 85ºF fueled explosive development within the system. Laura jumped from a low-end Category 1 hurricane with winds around 75 mph to a high-end Category 4 storm at landfall with winds approaching 150 mph only 24 hours later. As mentioned before, Laura became the strongest tropical system to ever make landfall in the state of Louisiana after this rapid strengthening.

Hurricane Sally

Noticing a theme here? Hurricane Sally was yet another storm to rapidly intensify over the Gulf, reaching high-end Category 2 hurricane status only a day after weakening into a low-end Category 1 off the coast of Florida. Sally made landfall near Pensacola, Florida with winds of 105 mph.

Hurricane Teddy

The second major hurricane of the year never directly impacted the United States, but was notable due to its rapid intensification outside of the Gulf of Mexico. Running into warm waters north of the Caribbean, Teddy strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph after being a low-end Category 1 hurricane only the day before. After slamming into the island of Bermuda, Teddy turned out to sea and dissipated northeast of Canada on September 23.

While these storms did end up severely impacting the areas where they made landfall, many of the other storms this year have failed to impress. Clearly, SSTs are not the only factor that goes into tropical cyclone development, or we may have seen even more monster storms.

Wind Shear

Other than interaction with land, wind shear may be one of the most prolific hurricane killers on planet Earth. Wind shear is simply a changing of wind direction and speed with height. While wind shear is a key factor in developing, strengthening, and organizing non-tropical thunderstorms, it is nothing but bad news for tropical systems. Hurricanes and tropical storms need calm winds to keep its larger circulation and thunderstorms around its center. When the core of a tropical system is exposed, it can easily get torn apart by wind shear, which leads to a complete collapse of the storm.

NOAA has noted that this year’s wind shear has been considerably weaker than in years past. While this may be true, there have been explosions of wind shear in critical areas that have either significantly weakened a storm or completely torn a system apart. Here are some examples of storms that never were or could’ve been noticeably stronger if wind shear hadn’t impacted its circulation.

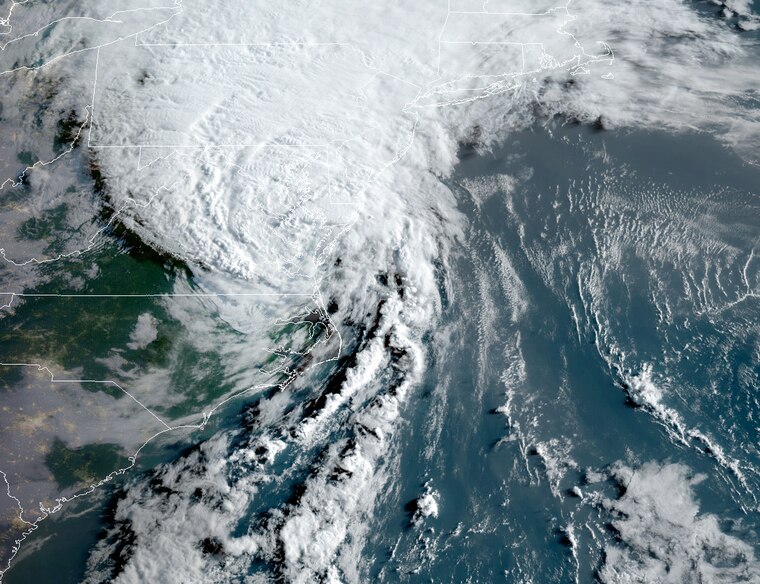

Hurricane Isaias

For us Carolinians, Hurricane Isaias was likely the most memorable storm so far this year. Isaias made landfall in Brunswick County, NC, as a Category 1 hurricane, but it could’ve been a lot stronger. Isaias drifted north out of the Caribbean in early August as a tropical storm and found itself in abnormally warm waters in the mid-80s, yet could never seem to get its act together. Strong wind shear along a frontal system sweeping through the eastern United States continually battered the tropical storm, which barely managed to attain Category 1 status 24 hours before making landfall. Every time an eye feature began to form on radar, it was swept away by strong wind shear from its western flank. Without much in terms of clouds, storms, and moisture to protect its exposed core, it never reached winds higher than 85 mph in its eyewall.

Hurricane Marco

Despite crossing over nearly the exact same area with the exact same SSTs only days apart in the Gulf of Mexico, Hurricane Marco and Hurricane Laura were drastically different storms. Marco was a prime example of wind shear tearing a storm apart before anything could get going. Marco was looking dangerous on the morning of August 23, but wind shear reached into the system and tore it apart before any further strengthening occurred. Once shearing winds blew apart the outer bands of the hurricane and reached the core, it was curtains for Marco. Even though fears were being raised of back-to-back major hurricane landfalls only mere days apart from each other in the Gulf, Marco relapsed into a weak tropical storm and fell apart after only delivering a glancing blow to the Bayou State.

Both Marco and Isaias were looking like they could develop into monster storms in their prime, only to be cut down by wind shear hours later. Wind shear can be hard to predict, especially when it comes to tropical systems, but they can wreak havoc on hurricanes and tropical storms and throw a wrench in forecasts to those who need them.

Dry Air

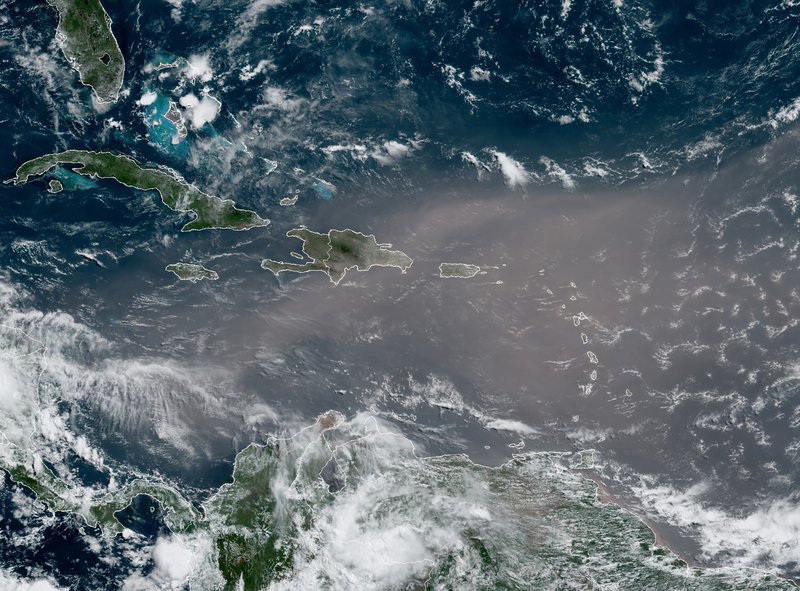

Remember the Saharan Dust Storm we saw back in June and July? That ended up having a huge impact on the tropics. From June 1 to July 4, we only saw one named storm form in the Atlantic. Cooler oceanic temperatures and wind shear had a hand in silencing the Atlantic Basin, but the main factor in the lack of development was the influence of dry air. As we know, hurricanes and tropical storms need moist, warm air to survive. Saharan dust is quite the opposite of that, as drier air associated with the dust is often cooler than the warm air at the surface of the ocean.

This satellite photo provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, shows a could of dust coming from the Sahara desert arriving to the Caribbean Monday, June 22, 2020. The massive cloud of dust is blanketing the Caribbean as it heads to the U.S. with a size and concentration level that meteorologists say hasn’t been seen in roughly half a century. (NOAA via AP)

Even outside of the dust storm we saw earlier this summer, dry air often inhibits growth and development of tropical systems. As storms draw near land, dry air often weakens storms shortly before landfall. Major hurricanes, such as Teddy and Laura, likely could have been even stronger without the presence of dry air.

At the end of the day, it’s rare to see hurricanes and tropical storms form at the rate they have been this year. 20 out of the 23 storms that have been named this year have become the earliest name storm of their respective letter ever. We have broken into the Greek alphabet for tropical systems for only the second time ever. Having said that, 15 of the 23 storms named so far have failed to reach even Category 1 hurricane status. Despite the record warmth in the Atlantic and a drop in wind shear, this season has been more about quantity rather than quality. There are even more factors that go into tropical development than the three that were listed above, but sometimes all it takes is a bit of luck for a hurricane season to go from an average year to something never seen before.