Measuring Mugginess: Why Dew Point Is King

In short: the higher the dew point, the muggier it feels.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — The drier times were nice while they lasted, but now the air you can wear is kicking us right in our derrières.

There are two ways meteorologists and weather apps measure mugginess: the more commonly used of which is known as relative humidity. It’s expressed as a percentage that represents how close the air is to condensation.

But here’s why relative humidity is… well, relatively useless.

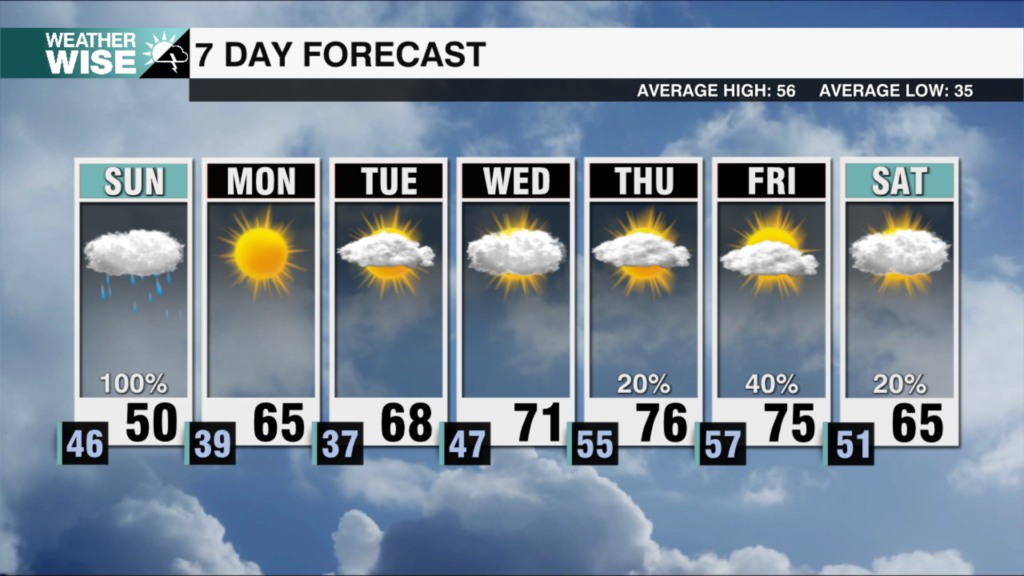

Take an average cloudy winter day in the Carolinas. Let’s say the temperature is 50 degrees with a dew point of 40 degrees. The relative humidity of this hypothetical day would be about 70%.

Now, take a sunny summer day like today, with a high of roughly 90 degrees and a dew point approaching 65. The RH here would only be around 40%. Despite a 30% reduction in relative humidity, most people would agree that the summer day *feels* muggier.

The key here is that the dew point rose 25 degrees.

But, what *is* the dew point?

The dew point is the temperature at which the air reaches condensation. In other words, it’s an absolute measure of how much moisture is in the air. Take a room 20 feet long, by 20 feet wide, by 20 feet tall at room temperature and a dew point of 50 degrees. If you were to wring all of the moisture in this room out, you could fill a water bottle. Now, if we took the same room and raised the dew point 20 degrees, the moisture content — which is the humidity you feel — doubles regardless of the actual temperature.

Furthermore, the dew point can never rise above the air temperature. That’s why it rarely ever feels humid in the winter, and why the mugginess seems to never end in the summer.